Teachable AI Lab Manual

Our lab is committed to developing a positive lab culture where individuals are supported and invested in the lab mission. To support this commitment, we have created this manual to describe our lab, the cultural values we aspire to, and expectations for lab members.

- Welcome!

- Lab Purpose

- Expectations and Responsibilities

- Code of Conduct

- Lab Resources

- General Policies

- Funding

- Other Resources

Welcome!

It looks like you recently joined the Teachable AI Lab in Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech)’s School of Interactive Computing. That’s great! We’re really glad to have you here and will do what we can to make your time in the lab amazing. We hope you’ll learn a lot about human-computer interaction, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and computer science, develop new skills (coding, data analysis, writing, giving talks), make new friends, and have a great deal of fun throughout the whole process.

This lab manual was inspired by several others, and borrows heavily from them (e.g., this one, this one, and this one). It’s also a work in progress. If you have ideas about things to add, or what to clarify, talk to me (Chris, the PI).

When you join the lab, you’re expected to read this manual. You’re also highly encouraged to read it while deciding if you want to join the lab in the first place. You should always feel free to talk to Chris to clarify anything in the lab manual and let him know if he isn’t following through on some of his promises! This lab manual is intended to be a starting point for a positive mentor-mentee and lab experience — but, ultimately, positive experiences will also require active investment in, and refinement of, our one-on-one interactions over time.

This lab manual is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial 4.0 International License. If you’re a PI or a trainee in a different lab and want to write your own lab manual, feel free to take inspiration from this one (and cite us!).

Lab Purpose

Mission Statement

To understand how people teach and learn and build machines that can teach and learn like people do.

Research Thrusts

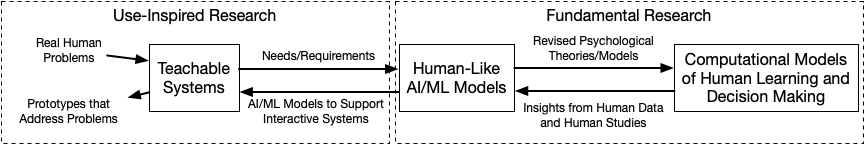

Thrust 1: Teachable Systems

How do we build systems people can teach and interact with, like they would another human, while still taking advantage of key non-human features of AI/ML systems?

Thrust 2: Human-like AI/ML

How do we develop cognitive systems that can learn like humans (incrementally, with few examples, etc.) and that produce human relatable/explainable/understandable outputs? The emphasis will be on both developing distinct AI and ML components as well as on putting these components together to create integrated systems.

Thrust 3: Computational Models of Human Learning:

How can we leverage human data to guide human-like computational model design? How can we leverage these human-like models to better understand human decision making and learning?

See this other page on the lab vision for more details.

Expectations and Responsibilities

Everyone

The following applies to all full-time, part-time, and undergraduate lab members.

Big Picture

Science is hard. But it’s also fun. In the Teachable AI Lab, we want to make sure that everyone experiences a positive, engaging, hostility-free, challenging, and rewarding lab environment. To maintain that environment, we all have to do a few things.

- Work on what you’re passionate about, work hard at it, and be proud of it. Be so proud of it that you have to suppress bragging (but it’s ok to brag sometimes).

- Scientists have to be careful. Don’t rush your work. Think about it. Implement it. Double and triple check it. Incorporate sanity checks. Ask others to look at your code or data if you need help or something looks off. It’s ok to makes mistakes, but mistakes shouldn’t be because of carelessness or rushed work.

- If you do make a mistake, you should definitely tell your collaborators (if they have already seen the results, and especially if the paper is being written up, is already submitted, or already accepted). We admit our mistakes, and then we correct them and move on.

- We all want to get papers published and do great things. But we do this honestly. It is never ok to plagiarize, tamper with data, make up data, omit data, or fudge results in any way. Science is about finding out the truth, and null results and unexpected results are still important. This can’t be emphasized enough: no academic misconduct!

- Support your fellow lab-mates. Help them out if they need help (even if you are not on the project) and let them vent when they need to. Science is collaborative, not competitive. Help others, and you can expect others to help you when you need it.

- Respect your fellow lab-mates. Respect their strengths and weaknesses, respect their desire for quiet if they need it, and for support and a kind ear when they need that. Respect their culture, their religion, their beliefs, their sexual orientation.

- If you’re struggling, tell someone (feel free to tell Chris!). Your health and happiness come first. The lab looks out for the well-being of all its members. We are here to help. It’s ok to go through hard patches (we all do), but you shouldn’t feel shy about asking for help or just venting.

- If there is any tension or hostility in the lab, something has to be done about it immediately. We can’t thrive in an environment we aren’t comfortable in, and disrespect or rudeness will not be tolerated in the lab. If you don’t feel comfortable confronting the person in question, tell Chris. In any case, tell Chris.

- If you have a problem with Chris and are comfortable telling him about it, do! If you are not comfortable, then tell another member of the department.

- Stay up to date on the latest research, by using RSS feeds and/or getting journal table of contents. Also consider following scientists in the field on Mastadon/Twitter.

- Have a life outside of the lab, take care of your mental and physical health, and don’t ever feel bad for taking time off work.

Small Picture

There are a few day-to-day things to keep in mind to keep the lab running smoothly.

- If you’re sick, stay home and take care of yourself. Because you need it, and also because others don’t need to get sick. If you’re sick, reschedule your meetings and participants for the day (or the next couple of days) as soon as you can.

- You are not expected to come into lab on weekends and holidays, and you are not expected to stay late at night. You are expected to get your work done (whatever time of day you like to do it).

- Show up to your meetings, show up to run your participants, show up to your classes, and show up to lab meetings. You do not have to be in at 9am every day – just show up for your commitments and work the hours you need to work to get stuff done.

- Dress code is casual (and you can dress up if you want!) but not too casual. When interacting with participants or presenting your work, don’t wear pajamas and sweatpants – but jeans are totally fine.

- Be on time. Especially when you are running participants – in fact, show up 15-20 minutes early to set everything up. And be on time for your meetings: respect that others have packed days and everyone’s time is valuable.

- When working remotely, you should be generally available over Slack during workdays (not necessarily responding immediately, but ideally within a few hours), and you should attend any scheduled remote lab meetings.

Principal Investigator

All of the above (see section on Everyone), and I promise to also…

- Support you (scientifically, emotionally, financially)

- Work with you to develop a mentoring and research plan tailored to your interests, needs, and career goals.

- We will meet before the Fall term each year (Aug/Sept) to create/update your 5-year plan (or whatever length is appropriate) that will keep you on track with your goals

- Before each term starts, we will review Objectives and Key Results (OKRs, a form of goal setting construct) from the previous term and create OKRs for the upcoming term

- Give you feedback on a timely basis, including feedback on project ideas, conference posters, talks, manuscripts, figures, and grants.

- Be available in person and via e-mail/slack on a regular basis, including regular meetings to discuss your research (and anything else you’d like to discuss)

- Give my perspective on where the lab is going, where the field is going, and tips about surviving and thriving in academia, industry, and other career paths

- Support your career development by introducing you to other researchers in the field, promoting your work at talks, writing recommendation letters for you, and letting you attend conferences as often as finances permit

- Help you prepare for the next step of your career, whether it’s a post-doc, a faculty job, or a job outside of academia

- Care about you as a person and not just a scientist. I am happy to discuss with you any concerns or life circumstances that may be influencing your work, but it is entirely up to you whether and what you want to share.

- Care for your emotional and physical well-being, and prioritize that above all else

Post-Docs

All of the above (see section on Everyone), and you will also be expected to…

- Develop your own independent line of research

- Help train and mentor students in the lab (both undergraduate and graduate) when they need it – either because they ask, or because I ask you to

- Present your work at departmental events, at other labs (if invited), and at conferences

- Apply for grants. Though I will only hire you if I can support you for at least one year, it’s in your best interest to get experience writing grants – and if you get them, you’ll be helping out the entire lab as well as yourself (because you’ll free up funds previously allocated to you)

- Apply for jobs (academic or otherwise) when you’re ready, but no later than the beginning of your 4th year of post-doc. If you think you’d like to leave academia, that’s completely ok – but you should still treat your post-doc seriously, and talk to me about how to best train for a job outside academia

- Challenge me (Chris) when I’m wrong or when your opinion is different, and treat the rest of the lab to your unique expertise

PhD Students

All of the above (see section on Everyone), and you will also be expected to…

- Develop your dissertation research. Your dissertation should have at least 3 substantial experiments that answer a big-picture question that you have. Much of your work has to be done independently but remember that others in lab (especially Chris!) are there to help you when you need it

- Help mentor undergraduate in the lab when they need it – either because they ask, or because I ask you to.

- Present your work at departmental events, at other labs (if invited), and at conferences

- Apply for fellowships (e.g., NSF GRFP, Facebook/Microsoft Fellowships). It’s a valuable experience, and best to get it early.

- Think about what you want for your career (academia – research or teaching, industry, government, startup, something else), and talk to Chris about it to make sure you’re getting the training you need for that career

- Make sure you meet all departmental deadlines (e.g., for your exams and thesis) – and make sure Chris is aware of them! They should be added to the 5-year plan that we create together.

- Prioritize time for research. Coursework and TAing are important, but ultimately your research will get you your PhD and prepare you for the next stage of your career.

Students Doing Independent Study (Undergraduate and Graduate)

All of the above (see section on Everyone), and you will also be expected to…

- Commit at least 12 hours / week to lab work under the guidance of your mentor

- Develop your weekly schedule by talking to your mentor. You should be coming in every week and scheduling enough time to get your work done.

- Communicate weekly with your mentor and provide them with updates on your progress

- Meet regularly with your mentor (every 1-2 weeks)

- Assist other lab members when needed

- Attend lab meetings when your schedule permits

- If you are doing a for-credit independent study, then you must also present at one of these lab meetings and submit a final write-up of your research by the end of the semester.

Code of Conduct

Essential Policies

The lab, and the university, is an environment that must be free of harassment and discrimination. All lab members are expected to abide by the Georgia Institute of Technology’s policies on discrimination and harassment, which you can (and must) read about here. Essential policies of Georgia Tech can be accessed here.

The lab is committed to ensuring a safe, friendly, and accepting environment for everybody. We will not tolerate any verbal or physical harassment or discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, disability, physical appearance, body size, race, or religion. We will not tolerate intimidation, stalking, following, unwanted photography or video recording, sustained disruption of talks or other events, inappropriate physical contact, and unwelcome sexual attention. Finally, it should go without saying that lewd language and behavior have no place in the lab, including any lab outings.

If you notice someone being harassed, or are harassed yourself, tell Chris immediately. If Chris is the cause of your concern, then reach out to the department chair or another trusted faculty member in the department.

Taking Photos & Videos

We respect the privacy and comfort of lab members by only taking photos or video recordings of them with their explicit knowledge and consent. This is especially important in situations where a lab member would otherwise not be aware of you taking a photo and therefore cannot object if they do not want you to – e.g., if they are wearing one of our VR headsets. To avoid ambiguity about when a lab member is vs. is not aware of photos being taken, we ask that everyone obtain consent from lab members before taking photos or videos and obtain consent again before posting any images on social media. This is done to respect others’ privacy and acknowledge that people have varying degrees of comfort related to being photographed and especially with having those photographs shared on social media.

The goal of this is to foster an environment where everyone feels safe to be who they are, take risks, and have fun, without worry or self-consciousness. If someone wants to be photographed doing something fun or silly in lab events, and consents to be photographed, by all means go ahead! Just please respect the privacy of those who do not want that.

On a related note, you cannot photograph your participants during an experiment. We do not have IRB approval to do this. If you would like a photograph of someone demonstrating your experiment, ask a lab member if they would feel comfortable being photographed while demonstrating what a participant does in an experiment.

Scientific Integrity

Research (Mis)conduct

The lab, and Georgia Tech, is committed to ensuring research integrity, and we take a hard line on research misconduct. We will not tolerate fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism. Read Georgia Tech’s policies on the conduct of research carefully (main page here).

A big problem is why people feel the need to engage in misconduct in the first place, and that’s a discussion that we can have. If you are feeling pressured to succeed (publish a lot, publish in high impact journals), you should reach out to Chris and we can talk about it – but this pressure is something we all face and is never an excuse to fabricate, falsify, or plagiarize. Also, think about the goal of science and why you are here: you’re here to arrive at the truth, to get as close as we can to facts about how people and machines teach and learn. Not only is research misconduct doing you a disservice, it’s also a disservice to the field. And it risks your entire career. It is never right and never worth it. Don’t do it.

Intellectual Property

Georgia Tech has a number of policies that govern ownership and commercialization of intellectual property created within the Teachable AI Lab and you should familiarize yourself with the intellectual property policy, found here.

The reality is that this policy is sometimes counter to the idea of completely free and open science. However, this is a policy that we all agreed to abide by when we joined Georgia Tech and each of us should make every good faith effort to do so. The intention of the policy is to protect the universities interest in intellectual property developed using university resources. Given that this policy somewhat impedes the open sharing of software, it is worth noting that in return for these restrictions, the university does provide some resources for patenting and commercializing the outputs of our lab that, in some case, may be worth exploring.

If you would like to release your code publicly under an open source software license or explore ways to commercialize software created in the lab, then speak to Chris about it and we can figure out the best pathway to try and make it happen.

Reproducible Research

If you gave someone else your raw data, they should be able to reproduce your results exactly. This is critical, because if they can’t reproduce your results, it suggests that one (or both) of you has made errors in the analysis, and the results can’t be trusted. Reproducible research is an essential part of science, and an expectation for all projects in the lab.

For results to be reproducible, the analysis pipeline must be organized and well documented. To meet these goals, you should take extensive notes on each step of your analysis pipeline. This means writing down how you did things every step of the way (and the order that you did things), from any pre-processing of the data, to running models, to statistical tests. It’s also worth mentioning that you should take detailed notes on your experimental design as well. Additionally, your code should also be well organized and clearly commented. We all know what it’s like to sit down, quickly write a bunch of code to run an analysis without taking time to comment it, and then having no idea what we did a few months down the road. Comment your code so that every step is understandable by an outsider. Finally, it is highly encouraged that you use some form of version control (e.g., Git in combination with GitHub) to keep track of what code changes you made and when you made them, as well as sharing code with others.

Reproducibility is related to replicability, which refers to whether your results can be obtained again with a different data set. That is, if someone ran your study again (with a different group of participants), do they get the same results? If someone ran a conceptually similar study, do they get the same results? Science grows and builds on replicable results – one-off findings don’t mean anything. Our goal is to produce research that is both reproducible and replicable.

Authorship

Like other labs, we will follow the Georgia Tech guidelines (here) as well as the APA guidelines with respect to authorship:

“Authorship should be based on whether the individual made a significant contribution, such as conceptualization, design, execution, and/or interpretation of the research study, as well as a willingness to take responsibility for the defense of the study should the need arise. In contrast, other individuals who participate in part of the study may be more appropriately acknowledged as having contributed certain advice, reagents, analyses, patient material, space, support, etc., but not listed as authors.

It is expected that each research group or laboratory will freely discuss and resolve questions of authorship before and during the course of a study. Each author should review fully material that is to be presented in public forums or submitted (originally or in revised form) for publication. The submitting author has the additional responsibility of coordinating the completion and submission of the work, satisfying pertinent rules of submission, and coordinating responses of the group to inquiries or challenges. The submitting author should assure that the contributions of all collaborators are appropriately recognized and must be able to certify that each author has reviewed and authorized the submission of the manuscript.”

At the start of a new project, the student or post-doc taking on the lead role can expect to be first author (talk to Chris about it if you aren’t sure). Chris will typically be the last author, unless the project is primarily under the guidance of another PI and Chris is involved as a secondary PI – then Chris will be second to last and the main PI will be last. Students and post-docs who help over the course of the project may be added to the author list depending on their contribution, and their placement will be discussed with all parties involved in the paper. If a student or post-doc takes on a project but subsequently hands it off to another student or post-doc, they will most likely lose first-authorship to that student or post-doc, unless co-first authorship is appropriate. All of these issues will be discussed openly, and you should feel free to bring them up if you are not sure of your authorship status or want to challenge it.

Old projects

If a student or post-doc collects a dataset but does not completely analyze it or write it up within 3 years after the end of data collection, Chris will re-assign the project (if appropriate) to another person to expedite publication. If a student or post-doc voluntarily relinquishes their rights to the project prior to the 3-year window, Chris will also re-assign the project to another individual. This policy is here to prevent data (especially expensive data) from remaining unpublished, while still giving priority to the person who collected the data initially.

Human Subjects Research

Adherence to approved IRB protocols is essential, and non-adherence can lead to severe consequences for the entire lab (i.e., we may lose permission to run any research on human participants). All lab members must read and comply with the IRB consent form and research summary for any project that they are working on. If you are not on the IRB, you cannot run participants, look at the data, analyze the data, or be in any way involved with the project.

Lab members must complete CITI Training and save their certificate. To be added to an existing IRB, talk to Chris and present him with your CITI certificate. If your project does not fall under the scope of a current IRB protocol, talk to Chris about writing a new one or filing an amendment to an existing one. You must ensure that you have IRB approval to run your study before you begin (which means that you either submitted an IRB protocol that got approved, or your name was added to an existing or amended IRB).

If a participant falls ill, becomes upset, has an accident with lab equipment, or experiences any problems while you are conducting your research, you must notify Chris as soon as possible. We may need to report this information to the IRB and/or funding agencies.

Lab Resources

Lab Website

The lab website) is, well, a website for the lab. It has much of the information you need to get started. When you join the lab you will be given access to edit pages on the lab. Edit it when you obtain information that will be useful for others to know! Ask one of the existing graduate students or Chris to be added as a member.

Slack

Slack will be used as the primary means of lab communication. The workspace we are using is: teachableailab.slack.com.

Try to keep each channel on topic, so that people can subscribe only to the channels that concern them. For messages to one person or a small group, use direct messages. If you have to send attachments (e.g., papers) or send messages that include out-of-lab recipients, use e-mail. If it’s an emergency and Chris isn’t responding on Slack, e-mail or text him.

Full-time lab members should install Slack on their computers and/or phones. Part-time lab members should also check Slack regularly. You should of course feel free to ignore Slack on evenings and weekends – and Chris probably will, too!

OneDrive

The lab has a shared One Drive Folder (“Teachable AI Lab”), which we can use to store documents and files for general lab use (e.g., weekly notes/slides, etc.). Contact Chris when you want to add something to the lab One Drive. The link to the folder is pinned in the general slack channel.

GitHub and GitLab

We will primarily use GitLab to share code within the Teachable AI Lab group (gitlab is currently transitioning from Drexel to Georgia Tech). If you do not have access to the GitLab group, then let Chris know what your GitLab username is and he can add you.

Additionally, GitHub can be used to share code, stimuli, and data with the world. However, it is important that you review the intellectual property policy and speak with Chris before sharing any lab related code on GitHub (you don’t want to inadvertently violate a university or lab policy). Additionally, only share data after you’ve spoken to Chris (we don’t want to share the data too soon, before you’ve had a chance to look at it thoroughly yourself).

General Policies

Hours

Being in lab is a good way of learning from others, helping others, building camaraderie, having fast and easy access to resources (and people) you need, and being relatively free from distractions at home (e.g., your bed or Netflix). That said, hours in academia are more flexible than other jobs – but you should still treat it as a real job (40 hours/week) and show up to the lab. My primary concern is that you get your work done, so if you find that you are more productive at home (lab mates can be chatty sometimes), feel free to work at home occasionally. If you have no meetings, no participants, and no other obligations that day, it might be a good day to work at home – but you can’t do this all the time, and I expect to see everyone in the lab on a regular basis.

For PhD students and those doing independent studies, I understand having to be away for classes and TA-ing, but show up to the lab on a regular basis when you don’t have those obligations.

To encourage lab interaction, try to be in most weekdays during ‘peak’ hours (assuming no other obligations) – e.g., between 11am and 4pm. This is not a hard rule, you can work at home occasionally, and I understand other obligations. But keep it in mind.

I’m a night owl and sometimes work during the weekends. This means that I will sometimes send emails or Slack messages outside of normal working hours. For the most part, I try not to, but sometimes I do. I do not expect you to respond until you are back at work (ignore me!). I do not expect there to be cases when I suddenly and urgently need something from you over the weekend (e.g., for a grant deadline), but should I anticipate that happening, I will bring it up in advance so we can plan accordingly. All this said, I realize that being told you can ignore my messages might not take away the stress of seeing my messages if you check work email or Slack in the evenings or on weekends. If my off-hours messages are unwelcome and cause distress, please talk to me, and I will be better at not bothering you during your time off.

Although I sometimes work weekends, I try to only do that when absolutely necessarily. Please respect that by making sure to give me enough heads-up about impending deadlines so that I can get things done for you (e.g., write letters of recommendation, give feedback on manuscripts, etc) while maintaining my work/life balance. For more details, see the Deadlines section below.

PI Office Hours

In addition to weekly meetings (see below), and occasionally dropping by the lab, you can find Chris in his office. His door is almost always open; if it is, feel free to ask for a chat. He will always say yes, though sometimes he can only spare a couple of minutes or might ask you to let him finish typing a sentence. If Chris has his door open, but is in a meeting with another student, then please be respectful and do not interrupt (unless you have a scheduled meeting, then please do interrupt!). If his door is closed, assume that Chris is either gone, in a meeting in his office, or does not want to be disturbed – so please send a message (Slack or e-mail) rather than knocking.

Meetings

Weekly Lab Meetings

Weekly lab meetings (~1 hour each) are meant to be a forum for trainees to present project ideas and/or data to get feedback from the rest of the group. Projects at any level of completion (or even not yet started!) can benefit from being presented. These lab meetings can also be used to talk about methods, statistical analyses, new papers, and career development. For paper discussions, everyone must come to lab meeting having read the paper and prepared with comments and questions to contribute. Some weeks we may explore a particular issue and have people read different papers – in that case, come to lab meeting having read your paper and be prepared to summarize it for the group.

Each trainee (students and post-docs) is expected to present at least once every semester. These meetings are informal, and you can do what you wish with your slot – just be prepared to contribute something substantive. Lab members are also expected to attend every meeting (obviously, illnesses, doctor appointments, family issues, etc. are a valid reason for missing a meeting). Undergraduate students are encouraged to attend as often as possible (assuming it fits in their course schedule).

Occasionally, we may have joint lab meetings with other faculty in the department – these may be combined with our weekly lab meeting or an additional meeting. We will also use lab meetings (or ad-hoc scheduled meetings) to prepare for conference presentations and give people feedback on job talks or other external presentations. Lab meeting agendas and notes will be kept in the #lab-meetings channel on Slack.

Individual Meetings

At the beginning of each semester, we will set a schedule for weekly meetings. Each full-time lab member (PhD students and post-docs) will have a one-hour slot set aside to meet with Chris. If scheduling conflicts arise (e.g., because of travel), we can try to reschedule for another day that week. If there is nothing to discuss, feel free to cancel the meeting or just drop by for a brief chat.

In general, Chris will not have regular meetings with independent study students; Instead, these students will have regular meetings with their post-docs and PhD student mentors.

Deadlines

One way of maintaining sanity in the academic work is to be as organized as possible. This is essential because disorganization doesn’t just hurt you, it hurts your collaborators and people whose help you need. When it comes to deadlines, tell your collaborators as soon as you know when a deadline is, and make sure they are aware of it the closer it gets. Don’t be afraid to bug them about it (yes, bug Chris as well).

Give Chris at least one week’s notice to do something with a hard deadline that doesn’t require a lot of time (e.g., reading/commenting on conference abstracts, filling out paperwork, etc.).

Give Chris at least two weeks’ notice (preferably more) to do something with a hard deadline that requires a moderate amount of time (e.g., a letter of recommendation).

If you want feedback on research and teaching statements, or other work that requires multiple back-and-forth interactions between you and Chris before a hard deadline, give him as much time as you can; at the very least three weeks.

For manuscript submissions and revisions (i.e., which either have no deadline at all or only a weak deadline), send drafts to Chris as soon as you have them, and bug him to give you feedback if he hasn’t responded in two weeks – papers are important!

Presentations

Learning to present your research is important. Very few people will read your papers carefully (sad, but true) but you can reach a lot of people at conference talks and posters. Also, if you plan on staying in academia, getting a post-doc position and getting a faculty position both significantly depend on your ability to present your data. Even if you want to leave academia, presentations are likely to be an important part of your job. Additionally, every time you present your work, you are representing not just yourself but the entire lab.

It is therefore highly encouraged that you seek out opportunities to present your research, whether it is at departmental talk series and events, to other labs (within or outside of Georgia Tech), at conferences, or to the general public. If you are going to give a presentation (a poster or a talk), be prepared to give a practice presentation to the lab at least one week ahead of time (two weeks or more are advisable for conference presentations, and many weeks ahead of time are advisable for job talks, which require much refining). Practice talks will help you feel comfortable with your presentation and will also allow you to get feedback from the lab and implement those changes well in advance of your real presentation.

Templates for posters will be available, and you can use those as much or as little as you’d like. Some general rules for posters should be followed: minimize text as much as possible (if you wrote a paragraph, you’re doing it wrong), make figures and text large and easy to see at a distance, label your axes, and make sure different colors are easily discriminable. Other than that, go with your own style.

Chris is also happy to share slides from some of his talks if you would like to use a similar style. You’ll get a lot of feedback on your talks in any case, but other people’s slides might be helpful to you as you are setting up your talk. As with posters, feel free to go with your own style as long as it is polished and clear.

Lab Travel

The lab will typically pay for full-time lab members to present their work at major conferences (e.g., CHI, AAAI, EDM, AIED, ITS, ACS). In general, the work should be “new” in that it has not been presented previously, and it should be appropriate for the conference. This will usually result in one to two conferences per year. When I set our grant budgets, I estimate $1500 per trip, so your reimbursable costs should be around that amount or less. Meal costs will be reimbursed for people who are presenting work from the lab. The lab will also pay for new grad students and postdocs to attend one conference in their first year in lab (i.e., without presenting). If you wish to attend any other conference outside of these guidelines, under some circumstances I may be willing to have the lab reimburse you for the registration fee. If travel expenses are being paid off of a grant, additional restrictions may apply (talk to Chris). All of these guidelines, of course, depend on the availability of funds. Lab members are required to apply for other sources of funding available to them (e.g., departmental funds for grad students and conference travel awards).

Recommendation Letters

Letters of recommendation are extremely important for getting new positions and grants. You can count on Chris to write you a letter if you have been in the lab at least one year (it’s hard to really know someone if they have only been around for a few months). Exceptions can be made if students or post-docs are applying for fellowships shortly after starting in the lab.

If you need a letter, notify Chris as soon as possible with the deadline (see Deadlines section for guidance), your CV, and any relevant instructions for the content of the letter. If the letter is for a grant, also include your specific aims. If the letter is for a faculty position, also include your research and teaching statements. In some cases (especially if short notice is given), you may also be asked to submit a draft of a letter, which will be modified based on Chris’s experience with you, made more glamorous (people are much too humble about themselves!), and edited to add anything you left out that Chris thinks is important. This will ensure that the letter contains all the information you need, and that it is submitted on time.

Code and Data Management

Code Storage

Code will be stored on the lab’s GitLab (git lab is currently in transition from Drexel to GT)

Storing Active Datasets

Lab data can be stored in one of three places:

- Lab server(s): software, behavioral data, and (separately from data and coded so that data are not identifiable) electronic consent forms, demographics forms, questionnaires

- OneDrive folders can be used to share small datasets and/or code with collaborators

Although the servers are backed up, the backup is only on-site – so make extra backups! Each lab member should back up raw data and code needed to reproduce all analyses on an external hard drive or on a service like OneDrive. You should not store data locally on your computer (but having data in a Dropbox folder synced to your computer is ok).

Data Organization

Please create a folder on the Teachable AI Lab OneDrive shared folder under the “Projects” folder that contains all of the data and files for your project (e.g., Teachable AI Lab/Projects/ProjectName). When you leave the lab, your projects directories should be set up like this, or something similarly transparent, so that other people can look at your data and code. You must do this, otherwise your analysis pipeline and data structure will be uninterpretable to others once you leave, and this will slow everyone down (and cause us to bug you repeatedly to clean up your project directory or answer questions about it).

Archiving Inactive Datasets

Before you leave, or upon completion of a project, you must archive old datasets and back them up. This should be done in a number of ways. First, you are responsible for backing up your data continuously, on the external hard drive that was bought for you upon your arrival. If you did not get an external hard drive, ask Chris for one as soon as possible (see Storing Active Datasets, above). Second, upon submitting a paper to a journal, all datasets and code must be publicly shared. This can be done on OSF, GitHub, or other platforms (see the lab wiki for details). Finally, after a project is completed and the paper published in a peer-reviewed journal, move the project to the archive on the server. Talk to Chris about this first.

Open Science

We’re all for open science, so lab members are encouraged (well, to some degree required) to share their code and data with others, whether they are in the lab or outside of it. Within lab, you can share your code and data whenever you like. But do not share your code or data with the outside world until you think (and Chris agrees) that the lab has finished working with it. This gives us an opportunity to work with the data to meet our needs (including grant needs!) before releasing it for other people to use. Generally, we will make our data and analysis code publicly available simultaneously with the submission of the paper to a peer-reviewed journal (exceptions might be made if work on the dataset is ongoing for a different paper). Additionally, there may be some restrictions with respect to sharing code, as outlined in the intellectual property policy. If you have any questions about sharing code or data then talk to Chris. Currently, the best option for sharing smaller datasets might be the Open Science Framework, but depending on the type of data we might also use platforms such as DataShop.

We will also share our work with the world as soon as we ready, which means preprints! The lab policy is to upload a preprint of a manuscript simultaneously with initial submission to a journal. The preferred preprint server is arXiv. We will also put PDFs of all our papers on the lab website, and you can and should share PDFs of your paper on your website and with whoever asks.

Funding

Funding for the lab currently comes from Chris’s start-up package from Georgia Tech and a DARPA AI Exploration award. If you need to buy something, or have to charge a grant for something, let Chris know and he will oversee the process.

At some point, you will likely be asked to provide a figure or two for a grant Chris is writing, and/or provide feedback on the grant. Relatedly, you are entitled to read any grant Chris has submitted, whether it is ultimately funded or not. Aside from being a good opportunity to learn how grants are written, this will also allow you to see his vision for the lab in the years ahead. Feel free to ask Chris to see any of his grants.

Funding for the lab comes from a variety of sources, including federal agencies (e.g., NSF, DoD, etc.), private foundations (e.g., Gates Foundation), and internal funds from Georgia Tech. I will oversee all aspects of the financial management of our funding sources. However, it is important to me to be transparent about where research money comes from and how it’s spent. You can find some details on our internal lab website, but please do not hesitate to ask if you want to know more details. In general, external funds tend to be restricted to expenses related to a particular project or set of projects, whereas some of the internal funds are flexible in that they can be used for any justifiable work-related purpose.

All research funded by external grants must acknowledge the funding agency and grant number upon publication. This is essential for documenting that we are turning their money into research findings. We must also submit a yearly progress report describing what we have accomplished. Lab members involved in the research will be asked to contribute to the progress report.